CONTENTS

8.1 The First Roads through Oxford........................................................................................... 2

8.2 Medieval and Tudor Highways and

Bridges.......................................................................... 3

8.2.1 Roads East of Oxford.................................................................................................... 3

8.2.2 Roads West of Oxford................................................................................................... 4

8.2.3 Roads South of Oxford.................................................................................................. 5

8.2.4 Roads North of Oxford.................................................................................................. 5

8.3 Seventeenth and Eighteenth

Century Roads.......................................................................... 5

8.4 Road and Bridge Maintenance

around Oxford...................................................................... 6

8.4.1 Hermits & Statute Labour............................................................................................... 6

8.4.2 Oxford Mileways & other

Highways.............................................................................. 7

8.5 The Turnpikes....................................................................................................................... 7

8.6 The Stokenchurch, Wheatley,

Begbroke & New Woodstock Turnpike................................. 8

8.6.1 Relevance of the Road................................................................................................... 8

8.6.2 Officers of the Trust...................................................................................................... 9

8.6.3 Acts for Renewal and New

Roadworks........................................................................ 10

8.6.3.1 Acts of 1740, 1762 and 1778................................................................................ 10

8.6 3.2 The New Road through

Headington....................................................................... 11

8.6.4 McAdam’s Improvements............................................................................................ 12

8.6 4.1 Major Projects at

Stokenchurch, Tetsworth, Wheatley & Bayswater...................... 12

8.6 4.2 Other Engineering work......................................................................................... 13

8.6.5 Toll Gates..................................................................................................................... 14

8.6.5.1 The Main Gates..................................................................................................... 14

8.6.5.2 Other Gates............................................................................................................ 15

8.6.6 Toll Income.................................................................................................................. 15

8.6.6.1 Tolls & Traffic...................................................................................................... 15

8.6.6.2 Toll Collection....................................................................................................... 16

8.6.6.3 The Lessees of Tolls.............................................................................................. 17

8.6.7 Expenditure.................................................................................................................. 17

8.7 St Clement's Turnpike Gate

& the Henley Road................................................................. 18

8.7.1 The Road along the Thames

Valley.............................................................................. 18

8.7.2 Oxford Improvement Act............................................................................................. 18

8.7.3 The St Clement’s Trust................................................................................................. 19

8.7.3.1 Improvements at Magdalen

Bridge........................................................................ 19

8.7.3.2 Financial Irregularities........................................................................................... 20

8.8 Turnpike Roads to the West................................................................................................ 20

8.8.1 The Cotswold Road...................................................................................................... 20

8.8.2 Crickley Hill &

Campsfield Turnpike.......................................................................... 21

8.8.2.1 The Initial Act over Two

Counties......................................................................... 21

8.8.2.2 Operating the Trust................................................................................................ 22

8.8.3 Botley, Fyfleld &

Newlands Turnpike......................................................................... 23

8.8.3.1 Swinford Bridge.................................................................................................... 23

8.8.3.2 Roads from Botley to Witney................................................................................ 24

8.8.3.3 Botley to Fyfield Road.......................................................................................... 25

8.9 Turnpikes South from Oxford............................................................................................ 25

8.10 Turnpikes North from Oxford.......................................................................................... 26

8.10.1 Woodstock & Rollright

Lane Turnpike...................................................................... 26

8.10.2 Charlbury Roads........................................................................................................ 27

8.10.3 Kidlington & Deddington

Turnpike............................................................................ 27

8.10.4 Turnpikes through Gosford

and Weston on the Green............................................... 28

8.11 Decline of the Turnpikes and

Modern Developments....................................................... 28

8.11.1 Financial Problems for the

Stokenchurch & Woodstock Turnpike............................. 28

8.11.2 Surviving Evidence of

Turnpikes............................................................................... 29

Sources..................................................................................................................................... 30

RUTV

8 is booklet number 8 in a series on the turnpike roads of Oxfordshire and

adjoining areas.

Turnpike Roads Around Oxford

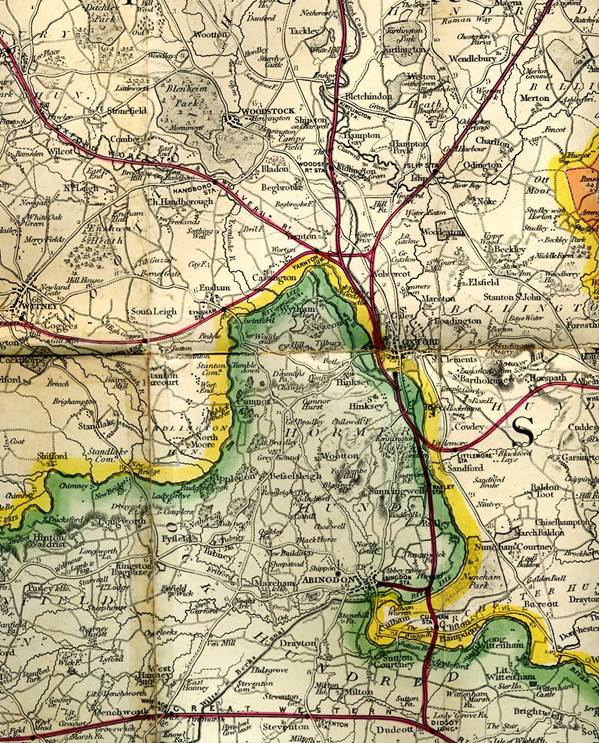

8.1 The First Roads through Oxford

The Thames is a formidable barrier for travellers between the Midlands and southern England. The great curves of the river valley formed the border between Celtic territories, later became a frontier separating the Saxon kingdoms of Mercia and Wessex. For many centuries it was to be the boundary between the old counties of Berkshire and Oxfordshire. A bold traveller could cross the river at several places on the wide flood plain where Oxford now stands. Prior to improvement of the river navigation by the Thames Commissioners, the many streams and islets at the confluence of the Thames and Cherwell created a wide expanse of slow flowing water in relatively shallow channels which could be crossed by a series of fords. Early travellers along the Corallian ridgeway no doubt took advantage of these (Figure 8.la). Medieval records refer to a regia via that followed the line of the ridge from Brill, through Forest Hill (named from the old English for hill ridge) to Oxford (VHCO 4; 123). Although Roman trade roads probably crossed the river here, there was no urban settlement close to the fords. Roman potteries flourished away from the river around Cowley and Headington to the east and around Boars Hill to the west. A major Roman road from the regional centre at Dorchester to Alchester was built along the high ground to the east on the Cherwell. Akeman Street, the principal east/west road in the region, ran well to the north, along the edge of the Cotswolds and through Alchester/Bicester, crossing tributaries to the Thames where they were still minor streams. There is strong evidence for a secondary road running south-west from the Hinksey ford towards Frilford. Margery (1973) has speculated that the routes which were to form the main east/west and north/south roads through Oxford are also Roman in origin. Although Roman traders may have travelled this way, it is unlikely that these tracks would have carried sufficient traffic to justify the attention of Roman road engineers.

About 727A.D. the Saxons

created the permanent settlement beside the main ford of the Thames (Hassell

1987) and in 912 the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle refers to Oxnaforda (Davis 1973). An

artificial embankment leading to the ford, thought to have been built in the

8th century, and a stone ford, dating from the 9th century, have been found on

the north bank of the river below St

Aldate's. This seems to be the main Langford crossing over a number of

streams and islets that were formed where the river cut through earlier gravel

deposits (Figure 8.2). Once established, the new Saxon town and monastic

foundations on the north bank of the Thames eclipsed the Roman town of Dorchester

to become the chief trading and ecclesiastical centre of the south

Midlands. The Thames was a disputed

frontier between Mercia and Wessex and so Oxford had strategic importance

controlling travel between the northern and southern banks of the river. Alfred's son, Edward the Elder was probably

responsible for laying out the basic street plan of the defended burgh at the

southern end of the dry gravel ridge between the Thames and the Cherwell

(Hassell 1987). Traffic from the

Cotswolds was funnelled through Oxford to several fords over both rivers. There were three principal places where the

Thames could be crossed. The most

northerly of these was at Godstow. A second, further downstream at Osney, had

branches to Seacourt and towards North Hinksey.

The southerly crossing was at an inflection of the river close to the

confluence with the Cherwell (Figure 8.2). Here the main stream is approached

directly across the river gravels rather than across the alluvial flood

plain. This southern ford was conveniently

situated on a direct route between the Mercian centre at Northampton and the

Channel port of Southampton in Wessex.

This highway, mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, may have crossed

the Cherwell at Gosford, entered the north gate of Oxford and passed through

the south gate over the Thames to the Berkshire bank (Figure 8.1b). From

Hinksey the highway ran south, probably along the old Roman road via Foxcombe

Hill and Wootton to cross the Ock at Abingdon.

Timbers and stones would have

been used to stabilise the river bed at the main ford. The Saxon's may have built a simple bridge

beside the ford but the low lying ground and minor streams to the south would

still have presented travellers with problems until a full causeway was

built. Although St Frideswide's Abbey

was close by, Abingdon Abbey, which owned land on the Berkshire side, had

particular interests in maintaining the bridge that eventually replaced the

ford.

8.2 Medieval and Tudor Highways and Bridges

Oxford grew and prospered through trade and manufacture, benefiting from its good access to primary agricultural products. The corn and wool from the county were a source of wealth that made Oxford the eighth largest provincial town in England by 1334 (Cooper 1979). The royal castle at Oxford, estate at Woodstock and hunting forest at Stowood gave added status to the area. Such an important regional centre needed good communications to the capital of the new Kingdom of England and so roads to the east grew in importance at the expense of the older routes from the Midlands to the south coast. There are two primary land routes between Oxford and London, one over the Chilterns through Wycombe and Uxbridge, the second along the Thames valley. These complemented the river route along the meandering Thames. Although the river journey may have been longer, it was probably the preferred route for heavy loads until the late 16th century (Peberdy 1996).

Any road east from Oxford must

cross the Cherwell and then the Thame and may also have to cross the Thames as

it meanders towards London. The gravels

immediately east of Oxford made this an obvious place to crossing of the

Cherwell (Figure 8.2). There are three medieval bridges over the Thame to the

south-east of Oxford; at Wheatley, Chislehampton and Dorchester (Figure 8.1c),

all of which must have been on important roads towards the lower Thames. The oldest stone bridge across the middle

Thames is at Wallingford, beside the site of the royal castle. The bridges at Henley and Maidenhead were

built later, allowing travellers to avoid the long journey along the deep

curves of the main Thames valley.

8.2.1 Roads East of Oxford

It is clear from an analysis of

the itineraries of the Plantagenet kings that in the 12th to the 14th centuries

the principal road approaching Oxford from the east was the route from

Wallingford (see RUTV 9). The royal

travellers from Windsor or Westminster passed through Reading, crossed to the

northern bank of the Thames by Wallingford Bridge and then bridged the Thame at

Dorchester. By the late medieval period

the new bridges at Henley and Maidenhead brought Oxford-bound traffic further

north (Figure 8.1c) but the traveller still had to cross the lower reaches of

the Thame. The bridges at either

Chislehampton or Dorchester were convenient for those wishing to reach Oxford

and John Leland in the 1530s used both during his travels in the Thames valley

(Toulmin Smith 1964). Pontage was

granted for Chislehampton Bridge in 1444.

Leland said he "passid over 3

litle bridges of wood, wher under wer plaschsy piites of water of the

overflowing of Tame ryver, and then straite I rode over a great bridge under

the which the hole steame of Tame rennith.

Ther were a 5 great pillers of stone, apon the which was layid a timbre

bridge" (Toulmin Smith 1964).

The stonework of the existing bridge is probably late 16th century (VHCO

5, 5). In contrast, Dorchester

Bridge is first mentioned in 1146 and is described by Leland as "of a good lenghth: and a great stone causey

is made cum welle onto it. There be 5

principals arches in the bridge, and in the causey joining to the south ende of

it". A survey of 1348 mentions

a "way" to Oxford from

Dorchester (VHCO 5, 40). Since

Dorchester Bridge served traffic using the older route to London through

Wallingford, as well as the later route through Henley, this was always the

principal road. Even so, the

Chislehampton road was of some importance, despite the climb over a steep

section of the Chilterns.

The Chislehampton and

Dorchester routes used to merge well to the east of Oxford. The former came along Garsington Way and

crossed Cowley Marsh. The latter passed

through Littlemore and Temple Cowley to join the other road at St Bartholomew's

Hospital. A single road, sometimes

referred to as Londonyshe Street (Hibbert 1992) then ran along a causeway to St

Clement's where it met the Wycombe road.

All these routes approaching Oxford from the east crossed the Cherwell

by the Pettypont, later called Magdalen Bridge.

The original wooden bridge was mentioned in 1004. By the 16th century, this had been replaced

by a stone bridge that was described as being 500 feet long, having 20 arches

and deep cutwaters (VHCO 4, 284).

Although this river crossing is important in the development of Oxford,

its function is secondary to the more important crossing of the Thames along

the Grandpont.

The more northerly route from

Oxford to London across the Chilterns is much more hilly and did not achieve

prominence until the medieval period when better vehicles were available. The Gough map of 1360 shows this as the

highway from London to Gloucester and South Wales. The road does not have to bridge the Thames,

although it climbs steeply up to Shotover Plain to reach the ridgeway. Further

east it has an extremely steep climb up the scarp face of the Chilterns at

Stokenchurch and also traverses the deep valley of the Wye. It crosses the Thame at Herford (the herepath

ford, VHCO 5, 117) near Wheatley where there was an ancient bridge. The bridge was repaired with local stone in

1284 and was important not only for Oxford traffic but also for travellers to

the Cotswolds and Worcester. The Gough

map marks Tetsworth on the road to Wycombe, perhaps indicating that even before

the hermitage was established, it was an important stop on the road.

8.2.2 Roads West of Oxford

Robert d'Oilly was Warden of

the newly built Norman castle at Oxford until his death in 1092. He is credited with building the large bridge

and causeway leading from the south gate of the town; Wood thought the bridge

dated from 1085. It may be that d'Oilly

only improved an existing causeway but this Grandpont extended for a mile and

eventually had 42 arches (Davis 1973).

The fourth arch was converted into a drawbridge during the 15th century

but was later removed. However, the

gatehouse became a famous landmark (Figure 8.3), referred to as Fryer Bacon's

Study since it was said that Roger Bacon had studied the night sky from rooms

above the gate. In medieval times this

was the principal route from the Oxford for heavy traffic and armies heading

towards both the south and the west.

After crossing the main stream outside the south gate, the causeway ran

southwards to the end of the gravel terrace (Figure 8.2). It then turned west,

at what is now called Redbridge, to cross two streams at Mayweed ford and

Stanford (stoneford) before reaching the edge of the flood plain below Hinksey

Hill. Although the Grandpont was on the

old north/south route through Oxford, it also served travellers heading

westwards. An old Roman road ran from

Hinksey, across Foxcombe from where it was easy to reach the Corallian ridgeway

to Faringdon and the Thames crossing near Lechlade. This involved two river crossings, but it

avoided the long northern sweep of the Thames and the marshy ground in the

Evenlode valley. The road from Oxford

through Faringdon to Bristol on the Gough map must have gone over the

Grandpont. Leland used this route "From Oxford thorough the Southgate and

bridge of sundrie arches over Isis, and along causey in ulter. ripa in Barkshir

by a good quarter of a mile or more, and so up to Hinxey hille about a mile

from Oxford. From this place the hilly

grounde was mearely wooddy for the space of a mile: and thens 10 miles al by

chaumpain, and sum come, but most pasture, to Farington, standing in a stony

ground in the decline of an hille." (Toulmin Smith 1964).

The existence of the Grandpont

reduced the need for another crossing of the Thames in the vicinity of

Oxford. Although the important

ecclesiastical institutions of Osney Abbey and Godstow Nunnery were sited close

to alternative crossings, none rivalled the south gate route. The earliest roads west from Oxford took

circuitous paths over the broad and boggy alluvial ground to the north and

south of the present Botley Road (Figure 8.2). The road serving Osney Abbey

used the Wereford or later Osney Bridge to cross the main stream. A subsidiary path then ran northwards across

the flood plain through Binsey to Seacourt on the far bank. The more important southern branch followed

an old stone causeway to a ford or ferry at North Hinksey (VHCO 4,

284). Leland travelled this road "from Oxford to Hinkesey fery a quartar of a

myle or more. Ther is a cawsey of stone

fro Oseney to the ferie, and in this cawsey be dyvers bridges of plankes. For there the streme of Isis breketh into

many armelets. The fery selfe is over

the principals arine or streame of Isis.

Beselles Legh a litle village is a 3 mile from Hinkesey fery in the

highe way from Oxford to Ferendune, alias Farington" (Toulmin Smith

1964). During the 16th century,

construction of Botley causeway and the Bulstake Bridge created a more direct,

safe route over the branches of the Thames and its flood-plain. Improvement of this series of causeways and

bridges was attributed partly to the charity of John Claymond. Another factor was the business interest of

Lord Williams who had acquired the Manor of Wytham after the dissolution of

Abingdon Abbey (Graham 1976). The new

highway carried traffic over to Cumnor Hill and from there along the Corallian

ridge to Faringdon. Nevertheless, to

reach Witney and the northern route across the Cotswolds to Cheltenham and

Gloucester, the traveller still had to use the ferry at either Eynsham or Bablock

Hythe. As a result, this route was

designated a horse road, unsuitable as a through-road for carriages.

The bridges over the two arms

of the river at Godstow are an enigma.

This crossing is the only one to the west of Oxford on Saxton's map of

1574. One of the existing bridges has a

pointed Gothic arch, evidence of a medieval origin. The bridges were probably in the care of

Godstow Nunnery, providing the ladies with a path over the Thames to the royal

residence at Woodstock. When the nunnery

was dissolved the property passed to the Duke of Marlborough and the bridge

seems to have lost any importance as a crossing for Oxford traffic. Presumably the Godstow crossing was too far

north to offer advantages over the Hanborough route to Witney or as route into

north Berkshire. In the 19th century the

City took a toll from users of these bridges to defray the cost of improving

the approaches on the Oxford side.

8.2.3 Roads South of Oxford

By the 13th century, bridges

over the Thames at Radcot and Newbridge provided a more convenient way south

from the Cotswolds for continental wool merchants bound for the Channel ports

(Figure 8.1b). To the south of Oxford the town of Abingdon had grown to

prominence with its large Abbey and its new bridge across the Thames was

carrying the east/west trade along the Gloucester Road. Hence, the trunk road south from Oxford lost

much of its earlier importance for trade although it remained a highway from

Oxford to important royal and ecclesiastical institutions around Salisbury and

Winchester.

8.2.4 Roads North of Oxford

Medieval roads running north

from Oxford declined in importance as the axis of trade became more

London-centred. Some traffic from the

Cotswolds and Gloucester may have turned south along the gravels to pass

through Oxford, but the steep climb on the London road to Shotover was a

disincentive to those who might descend from the high ridges. Wains carrying

cloth from Gloucestershire to London would have approached from Hanborough

where a medieval bridge across the Evenlode is mentioned in 1141. However, they would then have found it easier

to continue east over Campsfield to cross the Cherwell at Enslow and reach the

London road at Wheatley (Figure 8.1c). Other traffic from Worcestershire would

naturally keep to the high ground towards Islip and similarly head for Wheatley

Bridge.

Woodstock, the royal hunting

lodge north of Oxford, was probably a more important focus for medieval roads

than was the town on the river.

Proximity to the remains of Akeman Street meant that travel east/west

from Woodstock was relatively easy.

Traffic between Oxford and Woodstock would have used the road on the

ridge between the Thames and Cherwell, but would eventually have to cross one

or both of these streams. The King is

known to have passed through the east gate of Oxford and made his way through

the town to leave along the Woodstock road in 1339 (VHCO 4, 284). Oxford was a regional market for the

agricultural goods and so some traffic would have used the ridgeways beside the

Cherwell. Gosford is probably the most

important crossing for traffic coming south to Oxford and had a bridge in 1250

(VHCO 10, 159). Leland travelled

south from Banbury and Bicester (Bughchestar) through Islip to cross the

Cherwell by the Pettypont, presumably down the Marston road. He also mentioned Cherwell bridges at

Gosford, Emmeley and Heywood (Enslow and Heyford).

8.3 Seventeenth and Eighteenth Century Roads

From the 15th century onwards

Oxford declined in importance relative to other provincial towns but became

established as an academic centre. It

may be this latter factor, rather than its importance in trade, which led John

Ogilby to use Oxford as one of the important nodes for his road maps, published

in 1675. The majority of the routes

illustrated by Ogilby are still in use today, although there are interesting

differences in emphasis (Figure 8.4). The important radial route from London,

via Worcester, to Aberystwyth did not go through Oxford but kept to the high

ground, passing through Islip and Woodstock with only a branch road to

Oxford. Nor did the main trunk route

from London through Henley to Gloucester and St David’s go through Oxford but

favoured the Thames crossing at Abingdon.

The Oxford to Chichester road crossed Folly Bridge, as it had become

known, and Grandpont before following the old Roman road to reach Abingdon and

the south. This probably corresponds to

the Saxon trade route from Mercia to Wessex.

A short section of the old Northampton highway was followed by Ogilby's

road from Oxford, north to Bicester on the road to Cambridge; the Oxford to

Coventry road branched off near Weston on the Green. The Oxford to Salisbury road followed the

more modem road to Abingdon but the section from Milton Hill over the Downs is

now only a green road. Improvements to

Botley Causeway are apparent by the selection of this route for the Oxford to

Bristol road.

Ogilby's survey was copied by

other cartographers for almost two centuries and so any changes in the relative

importance of roads in the eighteenth century is difficult to judge. Examples of the road from London through

Worcester to Aberystwyth in Figure 8.5 are typical of the 18th century maps

using Ogilby's survey; the Senex map is identical with the Ogilby

original. Morden's map of 1695 drew

heavily on Ogilby's map but took into account comments from local experts. This map omits the Salisbury road but

includes the section of road from Benson to Oxford. The Henley to Oxford road seems to have

gained importance in Tudor times. This

was partly because it was an alternative route to London but also because

Henley was the head of navigation of the Thames for the large barges that could

not easily navigate the shallows, mill-dams and flash locks on the upper

reaches (Peberdy 1996). The journey

between London and Oxford can be shortened considerably by avoiding the long

meanderings of the river between Oxford and Reading. For instance the cloth used for a tapestry in

Magdalen College was shipped up river to Henley and then by cart to Oxford

(Anon 1968). King John had his plate

carted from Oxford to Henley for trans-shipment and Henry III had 30 tuns of

wine sent by river to Henley but carried from there to Woodstock by road

(Peberdy 1996) Improvements in the navigation as far as Culham in the mid-16th

century allowed larger barges to carry bulky goods closer to Oxford but the

round trip of 20 days by barge between Oxford & London took almost twice as

long as the river journey from Reading (Peberdy 1996). Hence, travel by road was often the most

practical means of transport for passengers and general goods. Bowen's map of 1755 (Figure 8.5) shows Oxford

at the hub of a road network serving both local and national needs.

8.4 Road and Bridge Maintenance around Oxford

8.4.1 Hermits & Statute Labour

During the medieval period most

travel was on horseback and overland goods were carried by packhorse. Any damage to the roadway was soon rectified

by natural processes and so highway maintenance was generally confined to the

care of bridges. The construction of new

bridges and the repair of existing crossings were frequently funded by

charitable bequests or occasionally by grant of a right to pontage. This allowed the holder to levy a toll on

those passing over and sometimes under, a bridge for a limited number of

years. The church itself had an interest

in maintaining the crossings close to its large houses and also acted as a

focus for charitable donations and gifts towards the repair of roads and

bridges. Hermits were often installed to

care for important bridges and to collects alms from travellers. Oxford's Pettypont was in the care of a

hermit in 1358 and at the Grandpont, in 1364, a hermit was installed at a

chapel to St Nicholas beside the bridge (VHCO 4, 248). On the road north of Oxford a hermit was

looking after the bridge over the Kingsbridge Brook at Freis as early as the

12th century (VHCO 10, 159).

Particularly important stretches of road were also looked after by

hermits. In 1447 a chapel to St John was

erected at Tetsworth with a resident hermit who was to use the labour of his

own hands to maintain the highway between Wheatley and Stokenchurch (VHCO 5,

147).

As trade grew and wheeled

vehicles were used instead of packhorses, roads through the town began to

suffer considerable damage. The area

outside the east gate was typical. The

weight of traffic carrying wood from Shotover, stone from Headington and

travellers from London had made it difficult to maintain a good roadway across

the wet ground at St Clement's. Three

grants of pavage were made by order of Richard II to encourage charitable

bequest for repairs to the road from Cherwell Bridge to Headington Hill (VHCO 7,

259). Wolsey had improved the road down

Headington Hill to facilitate the transport of building materials for Cardinal

College. However, the long-term

maintenance of the main highways and bridges was dependent on the charitable

funds generally organised through the various ecclesiastical institutions in

the area. These arrangements came to an abrupt end during the Reformation as

the chantries and monasteries and closed.

After a period of uncertainty

the means of maintaining roads was clarified by a series of Parliamentary Acts

during Elizabeth's reign. Each parish was given responsibility for maintaining

their own roads through what became known as statute labour. Each parishioner had to perform six days work

each year on repairing the parish roads. Those with property had to provide

teams (i.e. oxen or horses) to haul road-making materials. The parish had to

elect a local man to act as Surveyor to coordinate this labour. This system

worked well in rural parishes where the main need was to maintain lanes leading

to the fields or local mill. However, around urban areas where there was less

manual labour and teams and highways carried traffic into a market centre, the

Statute Labour was less capable of maintaining adequate roads.

8.4.2 Oxford Mileways & other Highways

Much of the damage done to the

roads of Oxford was caused by people from other parishes who came into

town. This iniquity was in part

remedied, in 1567, through the Oxford Mileways Act. This obliged those living

within five mile of the town to contribute labour for maintaining the roads and

bridges within one mile of Oxford. The

system was administered in four divisions and stones still mark the limits of

the Mileways at St Giles' to the north and Iffley Turn, Cheney Lane and

Headington Hill to the east. A map from

the 18th century shows that Botley Causeway was maintained under the

Mileways Act and in this case parishes across the Thames in Berkshire, such as

Eaton and North Hinksey, were included in the obligation to provide labour. The

principles on which the Oxford Mileways worked were similar to those that

guided the creation of turnpike trusts 150 years later, but in the 16th

century granting powers such as this to a town was very unusual and it is

intriguing as to why Oxford won such a privilege.

The remaining Mileway stones

date from the 17th century by which time the Mileways Act was less effective

and was resented since it placed no obligation on the residents of Oxford

itself. Nevertheless, the importance of

the St Clement's road into Oxford meant that the city did contribute to some

repairs. In 1592 the city reluctantly

paid for repairs at St Clement's prior to a royal visit but when more work was

necessary in 1614, they announced that this was done of "mere

goodwill" (Hibbert 1992). Much

still rested upon the parishioners. For

instance, the road from St Clement's church to the foot of Headington Hill was

pitched with stones in 1682. Flags of

Headington hardstone where used to pave the great holloway up the hill in 1725

but the road was so rough that members of the University created the raised

footpath that still survives today (VHCO 7, 259).

Although the problems within

Oxford were ameliorated, there was no general remedy on the main roads through

parishes outside the city. These

suffered the same fundamental problem of damage caused by through traffic. The old "London Way" from Stanton

St John to Wheatley Bridge past Stowood seems to have been maintained by

charity donations from users since in the 16th century there was in Forest Hill

parish "an honest poor olde man who

lived by opening the gate and asking a penny for God's sake" (VHCO 7,

123). An old milestone has been found

near Stowood, engraved "Here begins

Stowood High Way which ye County is to repair, 1680" (Lawrence 1977).

8.5 The Turnpikes

From the beginning of the 18th

century, turnpiking became a very effective means of ensuring that those who

used the road contributed directly to its upkeep and that the statute labour of

individual parishes was coordinated.

Trustees were appointed to improve a length of main road that passed

through several parishes. They were

empowered to erect turnpike gates, to levy tolls on travellers and use the

money raised to improve and maintain the road as a whole. An Act of Parliament was necessary to create

these trusts that had a finite life. The

main roads radiating from London and carrying the heaviest traffic were the

first to be turnpiked. The highway

approaching Oxford from the east, over the Chilterns, was turnpiked from

Stokenchurch to Woodstock and Oxford in 1719 and then on from Woodstock to

Rollright in 1729 (Figure 8.7). The second route from London to Oxford, the

Henley Road, was taken under the care of a turnpike trust in 1736. This road was equally important as the main

Gloucester Road through Abingdon linking with the Fyfield to St John's Bridge

road that had been turnpiked in 1733.

The other main roads out of

Oxford were not turnpiked until the second wave of Parliamentary activity after

1750. This suggests that Oxford was not

then on a major route to places elsewhere in the Kingdom. The first turnpike road from Oxford to Witney

was approved in 1751 under the direction of the Crickley Hill & Campsfield

Trust. In order to avoid the Thames

flood plain, travellers had to go northwards from Oxford as far as Campsfield,

now Oxford airport, before turning west to bridge the Evenlode at Long

Hanborough. In 1755 the road from Fryer

Bacon's Study, outside the south gate, to Hinksey with the branches to Abingdon

and Faringdon were turnpiked. The road

to the north through Kidlington and Adderbury to Banbury was improved by an Act

of 1754 and that through Middleton Stoney to Towcester in 1756.

A third wave of turnpike

activity was associated with improvement of the river crossings. In 1767 the building of Swinford Bridge

caused major changes in the pattern of travel to the west of Oxford. Traffic used the new road over Botley

Causeway and the Swinford Bridge to reach Witney and the Cotswold Road more

directly. From the causeway, Oxford

traffic could also use the road westwards to Faringdon along the ridgeway. This made the old road over Foxcombe

redundant and meant that only traffic for Abingdon and the south continued to

use the Grandpont. The better road from

Botley also encouraged turnpiking of the Besselsleigh to Wantage road in

1771. The Oxford Improvement Act of 1771

allowed for the rebuilding of Magdalen Bridge and improvement of the roads

through St Clement's.

Finally minor improvements in

the network were dealt with either by amendments to existing trusts, such as

the new road through Headington in 1788, or by Acts covering short lengths of

new road such as from Kidlington to Weston, through Gosford which was turnpiked

in 1781.

The various turnpikes will be

dealt with in the same order as above; from the east, then west, south and

finally north (Figure 8.7). Several roads to the south of Oxford have been

dealt with in detail elsewhere; Besselsleigh in RUTV 4, the Abingdon and Henley

Roads in RUTV 7. Records from the Stokenchurch Trust have survived in the

Oxfordshire Record Office and so this turnpike will be dealt with in most

detail below. Some records from the last years of the St Clements Trust have

been lodged in the Bodleian Library.

8.6 The Stokenchurch, Wheatley, Begbroke & New Woodstock Turnpike

8.6.1 Relevance of the Road

For Ogilby, the road to

Worcester was the most important radial from London to the south Midlands. However, by the early 18th century,

Birmingham grew in prominence as the industrial revolution gathered momentum. Three routes to Birmingham were turnpiked in

the early 18th century. The most

important was through St Albans, Stony Stratford & Coventry, another

through Uxbridge, Wendover, Banbury & Warwick and the third from Uxbridge

through Stratford-upon-Avon passed closest to Oxford. The Uxbridge road was turnpiked in 1715 and

in consecutive Acts in 1719, trusts were established to cover the road from

Beaconsfield to Stokenchurch and from Stokenchurch down the steep face of the

Chilterns to Enslow Bridge and Woodstock, north of Oxford. As far as Oxfordshire this route was the old

Worcester Road but a branch near Chipping Norton carried traffic northwards

towards Birmingham. The branches from

Stratford to Birmingham and Stonebow Bridge to Worcester were turnpiked in 1726

and most other sections of the routes from London to Worcester and Birmingham

were in the care of turnpike trusts by 1731. The exceptions were roads high

upon the Cotswolds from Rollright to Long Compton and Bourton to Broadway. These were on well drained, limestone and so

did not suffer the same degree of damage from wheels as the roads in the wet

river valleys.

A Parliamentary Committee was

told that between Beaconsfield and Stokenchurch the road was frequented by

wagons and other heavy carriages and had become so very ruinous and out of

repair that in the winter season it was dangerous to travellers (JHC 19,

29). Evidence in support of the

Stokenchurch road was given to a Parliamentary Committee in 1717 by a group of

gentlemen from the area; Richard Carter, Thomas Cousins, William Lipscombe,

Richard Brown, Richard Hitchcott, Adam Bellinger (a wealthy wagoner from

Woodstock) and George Ryves (JHC 18, 707). The main points were reiterated in 1718 by Mr

Carter, Mr Beeson and Mr Weate (JHC 19, 20). They testified that "inhabitants of the several parishes have not

only constantly done more than their statute work, but also raised large sums

of money and duly applied the same towards repairing the roads and that proper

materials for amending the highways lie at a great distance from some parts of

the said road and that the petitioners have often been obliged to pay twelve

pence per load, at least, for stones".

This last statement is at odds with the evidence given by Mr McAdam a

century later but may indicate that inappropriate materials being used. For instance Plot in 1677 noted that the road

near Tetsworth was mended with local stone called maume, which unfortunately

broke up in the winter and "would

have been better for mending their land than the highway". The petitioners still viewed the road network

around Oxford in the same manner as Ogilby (Figure 8.4) and sought

responsibility for the great road to Worcester from Stokenchurch over the Thame

at Wheatley Bridge, crossing the River Ray at Islip and on to Enslow Bridge

over the Cherwell. This suggests that

the impetus for improvement came from long distance traffic from the west

Midlands through Woodstock rather than travellers to Oxford.

Nevertheless, the opportunity

to benefit from improvements to the Worcester road could not be missed by the

more progressive elements in Oxford. In

December 1718 several gentlemen, freeholders and others living on the north

side of Oxford petitioned Parliament.

They wished to have the road from Wheatley Bridge to the Mileway on the

south-west side of Oxford and from the Mileway on the north side of Oxford to

the Borough of New Woodstock included in the Act covering the Stokenchurch Road

(JHC 19, 31). The section from

Wheatley was only a branch road on Ogilby's map and its inclusion in the

petition suggests that in the early 18th century, Oxford was increasingly

important as a focus for routes from the Cotswolds. The petitioners stated the road into Oxford

was very frequently used by many heavy carriages and that parts were "so ruinous and fouderous that travellers

cannot pass with safety, though the statute-work hath been constantly done and

more than six pence in the pound raised and duly applied". The Committee considering the Bill agreed to

this plea and instructed that the branch roads as far west as St Clement's and

north of St Giles' be included in the Stokenchurch Roads Act. It is not clear why, at the same time, the

turnpike did not extend beyond Enslow Bridge so that the two branches

rejoined. Perhaps the quality of the

ground through Wootton made the road easier to maintain by normal parish duties

and local rates.

Over 150 individuals were named

as trustees in the first Act. They were

headed by local aristocrats and gentlemen such as Lord Harry Plowett, Hon.

James Bertie, Hon. Simon Harcourt, Sir

Francis Dashwood, Sir Thomas Read and Sir Thomas Tipping as well as clergy from

the parishes adjoining the road. They

were to hold their first meeting, before 10th April 1719, at the house known by

the sign of the White Hart in the town of Wheatley. There are records of meetings after 1740 and

these show that rarely more than ten trustees attended to deal with the normal

business of the trust, though the number of trustees was maintained by

appointing new individuals as older members left or died.

8.6.2 Officers of the Trust

The trust appointed several

paid officials (Table 8.1). The clerk administered the legal aspects of the

trust and arranged the leasing of tolls.

At the time of the 1788 Act, Paucefoot Cook of Watlington was clerk and

treasurer but the Act of 1788, like others of this period, specifically forbade

these two posts being held by the same person.

In the years around 1800 the trust had two clerks, both of them local

solicitors, John Hollier of Thame, and Henry John North of Woodstock. On the death of Mr Hollier Snr in 1820, John

Hollier Jnr and Henry North Jnr continued as clerks. John Marriott Davenport, one of the leading

solicitors in Oxford took over responsibility as clerk in 1867 and it is

through his care and attention that so many of the records of the trust have

survived. Messrs Morrell and later

Messrs Wootton of Oxford acted as treasurers for the trust after the separation

of the management functions.

The care of the roadway and the

buildings was the responsibility of the surveyor and his sub-surveyors. The surveyor obtained road-making materials

and organised the team and statute labour provided by the parishes to repair

the road. In later years he also managed

the contract labour and specified the requirements for the road and the

tollhouses. Evidence to Parliament in

1739 was given by Stephen Solesbury, John Morris and John Stone, who were

surveyors of different parts of the road. John Stone is mentioned most

frequently in the records after 1740. In

1757 the road was divided into four districts, each with a separate

surveyor. Appointments were made for (i)

Stokenchurch to Wheatley Bridge, (ii) the bridge as far as Cheney Lane on the

Shotover road and New Inn on the Islip road, (iii) Islip to Enslow Bridge and

(iv) Oxford to Woodstock. In 1778 John

Rogers was sub-surveyor for the sections from the Mileways as far as Woodstock

on one branch and Wheatley on the other.

He was responsible for constructing the new road at Headington, in 1788,

under the overall direction of the surveyor, Mr Weston. Richard Roberts, John Saywell and Jonah Bance

were the other three surveyors. Samuel

Weston resigned in 1802 and Thomas Fergerson of Stokenchurch became surveyor

from Stokenchurch to Wheatley while William Savours of Headington took

responsibility for the rest.

By the early 19th century turnpike trusts were seeking advice of professional road engineers rather than relying on local men to maintain the highway. The trustees invited Mr John Loudon McAdam to their meeting in November 1819 at the Crown Inn, Wheatley. They commissioned from him a report on how critical sections of the road might be improved. James McAdam (later knighted), the son of J.L. McAdam was subsequently appointed chief surveyor to the trust at a salary of £150/a. The McAdams had made their reputation improving the Bristol turnpikes and James was chief surveyor to the various trusts which controlled the Bath and Gloucester Roads through Colnbrook, Henley, Abingdon and Faringdon. He obviously acted as a consultant engineer relying on four local sub-surveyors, George Gibson, Wm Humphries, Thomas Goddard and Thomas Boiler, for day to day work. Most of McAdam's recommendations had been implemented by the 1830s when his salary was reduced to £100/a. Financial problems meant that by 1849, payments to McAdam had fallen to £33/a. James Clarke, who had been sub-surveyor at Headington in 1841 was appointed as both surveyor and collector of tolls in 1843 when the drop in traffic and lack of willing lessees meant that the trust took the collection of tolls into their own hands.

8.6.3 Acts for Renewal and New Roadworks

8.6.3.1 Acts of 1740, 1762 and 1778

The turnpike Act gave the

trustees powers for 21 years during which time it was assumed that the road

would be fully improved. However, like

most other trusts, the Stokenchurch trustees continued to renew and extend

their powers over a period of 160 years through a series of Parliamentary

Acts. The second Act in 1740 took in a

section of road from the Crown Alehouse, Stokenchurch, to the original limit of

the turnpike at the top of the hill.

John Bartlett told a Parliamentary Committee in 1739 that persons

travelling the half-mile stretch from the Crown benefited from the improvements

to Stokenchurch Hill without contributing.

Edward Clerk said that the trust had borrowed a considerable amount of

money to improve the whole road but that the loans had been paid off (JHC 23,

452). The surveyors described the

badness of the road before the 1719 Act and the good conditions since, but

thought it necessary for further assistance.

Interestingly this Act reduced the tolls; for instance that for a

carriage & six horses fell from 1s-6d to 1s. Its seems likely that local

pressure led to this legislative change since the trustees were at liberty to

change less than the specified amount if they chose and actual tolls may have

been lower than stated in the first Act.

The general perception of travellers seems to have been that Oxfordshire

turnpikes were not good value for money and in 1760 Arthur Young wrote that

they were "in a condition formidable

to the bones of all who travelled on wheels". He noted in particular that in 1768 the road

from Tetsworth to Oxford was "all

chalkstone of which everywhere loose ones are rolling about to lame

horses. It is full of holes and ruts

very deep". The trustees had

met in Wheatley during November 1769 and agreed that the road was in “indifferent condition, notwithstanding the

sums annually expended on its repair” (JOJ). This they concluded was due to

the narrowness of the road and its original construction and the following they

February sought proposals of contractors “for

widening and new-making or thorough repair of the road”. In September 1770 the trust arranged to

borrow “a further sum of money in order

to complete repair of the road”. However, the management of the road was

called into question by a letter from Simon Quack who wrote to the Oxford

Journal in October 1770 to complain about the poor drainage and deeply rutted

surface of the Stokenchurch Turnpike (Figure 8.13a).

The trust gave evidence to a Committee

in 1761 saying that the tolls were insufficient and the debt had risen to

£5,500 (JHC 29, 16, 25, 66 & 127).

Thomas Newell said that parts of the road were very narrow and

incommodious and extremely ruinous and bad.

The trust was also asked to take in the Mileways from Cheney Lane to the

foot of Headington Hill and from St Giles' Church northwards. The Mileways had been subject to more wear as

a result of the increase in wagon traffic coming through Oxford, particularly over

the previous ten years. It was

recommended that the tax of 4d per yard levied under the Mileways Act for the

roads towards Littlemore, Cowley, Wheatley, Woodstock and Kidlington be put

"in the care and management of the

commissioners of the several turnpike roads which abut them". Thomas Walker said that the eastern division,

which covered the three Mileways from St Clement's received £52/a and had a

balance of £120, whereas the northern division covering the two Mileways from

St Giles' received £38/a and had a balance of almost £22. The contribution from these rates was

presumably a factor in the Act of 1762 specifically forbidding the trust

erecting tollhouses close to the city.

By the time of the next renewal

in 1778 the Crown Alehouse had become a smithy.

There had been confusion about who was responsible for sections of the

Oxford Mileways abutting the turnpike.

This Act made it clear that the money for road maintenance levied on the

parishes of Cassington, Yamton, Godstow & Wolvercote, Ellsfield, Wood

Eaton, Forest Hill, Beckley, Marston, Islip and Wheatley (between £2 and £7

each) was to be managed by the trustees but this did not give then any other

rights over these sections. The trustees

were still meeting in the White Hart in Wheatley. Additional trustees named in this Act were

recognisable worthies from Oxfordshire; the Marquis of Blandford (George

Spencer), Lord Robert Spencer, Sir William Blackstone, Peregrine Bertie and

William Harcourt as well as the Vice Chancellor of the University and Mayor and

Recorder of the City of Oxford. By the

early 19th century trustees were meeting at the Crown in Wheatley with

occasional meetings at the White Hart in Tetsworth. Meetings were chaired by the most senior

person present, typically Lord Charles Spencer in 1808, but after 1811 the Earl

of Macclesfield was the most frequent chairman.

Other regular attendees were Thomas Shutz of Forest Hill, William Henry

Ashhurst of Waterstock and Revd Cranley Lancelot Kerby, the latter being a

prominent holder of bonds on loan to the trust.

8.6 3.2 The New Road through Headington

The renewal Act of 1788

included some radical changes to the turnpike route. From Wheatley the old road climbed the ridge

up to Shotover Plain and then descended the steep path to Cheney Lane (Figure

8.8). The gradient on these hills put a severe strain on horses and

passengers. Wood recorded that in 1689

Mathew Slade, a Dutch doctor, died in a stage coach "occasioned by his violent motion going up Shotover Hill on foot". The number of horses drawing a coach on any

highway was normally restricted to prevent heavy loads being dragged along the

road but in 1768 the trustees allowed up to 10 horses to be used on vehicles

from "the post to the 51st milestone

at the top of Shotover Hill". (vehicles ascending Littleworth, Stowood

and Wood Eaton Hills were granted similar concessions).

As early as 1773 the trustees

began to survey alternative routes that avoided the steep climb at

Shotover. A route that used the old

Mileway through Headington would involve some improvement of an existing road

but a new section would have to be built from Headington to Wheatley. The trust favoured following an existing

bridleway from Wheatley leaving the Islip road at the pits near to Mr Shutz's

gate, along Forest Hill Lane to the windmill in Headington Field and from there

to Cheney Lane (Figure 8.9). It was estimated that the distance from the Plough

at Wheatley Bridge to Cheney Lane was only greater by half a mile than the old

road. A presentation to a Committee in

1774 (JHC 34, 393) described the proposed route as going "through Holton and Forest Hill Inclosures,

over Headington Field and Headington Quarry to the turnpike road at or near the

52nd milestone beyond the bottom of Shotover Hill or else over Headington Field

and down Headington Hill to come into the said turnpike at a house called

Cabbage Hall." George White said that the trust had "made the ascent of Stokenchurch Hill and

Postcombe Hill considerably easier" and they now wished to improve the

road over Shotover. However, the trust

was paying 4.5% on bonds of £9,550, the treasurer had only £123 in the account

and income from tolls was about £1,500/a after paying the gatekeeper's

salary. It was presumably this poor

financial position that delayed action on the new road until the next decade

but there was also local opposition to any major change. A letter from "Philanderer" to the Oxford Journal in November 1774 (Figure

8.13a) highlighted the adverse economic impact on roadside businesses if the

route was changed and complained about the high cost of a totally new road.

In their submission for the

1788 Bill the trustees stated that "Shotover

is very steep and dangerous, whereby many accidents have happened to carriages

and travellers and from the situation of the road to the comer of Cheyney Lane,

leading towards Oxford, stage coaches and other carriages are frequently

overturned, and several persons have been killed, and others grievously hurt". They claimed that "it would be commodious and less dangerous to travellers, if, instead of

the road from the said comer of Cheyney Lane up Shotover Hill, and from thence

to the said highway leading to Holton, the road from the said comer up

Headington Hill over Headington and Shotover Commons to or near the village of

Forest Hill was sufficiently widened, altered, amended and completed, and a new

road made from thence, to join the said Enslow branch of the road at or near

the stone-pits belonging to Henry Whorwood, Esq., in the parish of Holton, in

the County of Oxford". They also

took powers to improve the narrow highway from the west end of the town of

Wheatley, across Wheatley Field to Holton so as to join the two branches of the

road. Once these improvements were

complete, the Shotover road and the section of the Enslow branch between the

junction of the branches and the new communication road at Wheatley would no

longer be turnpikes.

The trust received two

estimates from Mr Weston, their surveyor, for constructing this new road by

improving the old bridleway from Headington to Forest Hill. In June 1789 they accepted the estimate of

£l,784 for the work. The roadway was to

be 42 feet wide and the trees were to be taken down on the south side (to assist

in keeping the roadway dry). In addition

the trust agreed that John Rogers should make a road on the other branch of the

road over Campsfield "from the six

milestone to the hither end of the Oxford Lane leading to Woodstock, about 6

furlongs" (Figure 8.8). However, during the following year Mr Rogers,

was found to have done an unsatisfactory job on the new sections at Headington

and on the Woodstock road. The trust

would not settle Mr Weston's accounts until the road was 12 inches in stone on

a 24 feet carriageway. The work must

have been complete by 1793 when the trust asked that "the milestones be new faced and set up at the proper distances on the

whole of the road and new stones provided where necessary". It may be assumed that most of the milestone

which survive alongside the old A40 date from this period (RUTV 10). The milestones were regularly re-painted or

re-lettered; this had been done in 1767, and in 1822 John Butler was paid

£3/12/- for painting and writing the milestones installed in 1793.

8.6.4 McAdam’s Improvements

8.6 4.1 Major Projects at Stokenchurch, Tetsworth, Wheatley & Bayswater

In the early years of the 19th

century the trustees sought to improve the section of road across the ancient

bridge near Wheatley. In 1801 they made

a request to the county to widen Wheatley Bridge and when the improvements were

completed in 1807, the trust covered half the cost of £1057 and paid for "the watching of Wheatley Bridge while

rendered dangerous during repair of the parapet wall".

A major phase of improvement

began after Mr McAdam was taken on as chief surveyor. His report to the Stokenchurch Trustees in

1819 concluded that there were few fundamental problems on the road. McAdam said that, "with the exception of space between Oxford and Begbroke, the districts

abound with materials, some of excellent quality and all sufficiently good to

ensure the foundations of a hard, smooth, solid and durable road". He advised a mix of stone with gravel for the

Oxford to Begbroke road and thought that the Oxford Canal could provide

transport facilities that might also carry cheaper materials for Begbroke to

Woodstock. He felt that road making

materials were not being prepared or selected "and are thrown upon the road in a very foul and improper state,

rendering the road extremely rough, loose and heavy". He recommended lifting the roadway from

Oxford to Stokenchurch, paying attention to raking the surface until it became

perfectly solid and level. McAdam

recognised the importance of good drainage and he recommended to the

Stokenchurch Trust that "ditches

needed cleaning and hedges and trees cut in order that water may immediately

discharge from the road" and that provision be made for disposal of

road scrapings. He thought that work to

improve the road would afford employment during the winter and spring for poor

labourers in the parishes and that the repair costs need not exceed £2,600 in

the first year, diminishing later.

Some improvements to critical

sections of the road were instituted soon after McAdam's arrival. The holloway at Chilworth was widened at a

cost of £165 in 1822. In subsequent years,

McAdam proposed grander improvements to the eastern sections of the road

(Figure 8.9). Plans were discussed to reduce Postcomb Hill and improve the road

through Tetsworth; one possibility was to take the road along the Thame & Postcomb

Turnpike through Atlington and then to the Royal Oak at Tetsworth. The plans were amended and considered with a

proposal to change the road from Stokenchurch to run over the common and

through Cockshoot Wood. A third element

in the plan was to build a link road from the Enslow/Islip branch, through

Bayswater to Headington. The

Stokenchurch and Bayswater plans alone were estimated at £5,000 and the trust

appointed George Smith and William Bough of Bath as the contractor for all the

Tetsworth, Stokenchurch and Bayswater schemes.

The proposals were incorporated into the 1824 Act which said that "the present road leading over the hill in

the parish of Aston Rowant is inconvenient and it will be more commodious to

the public if the course of the road were altered or diverted at the summit of

the hill, through woodland and other land in the parish of Aston Rowant to join

the present road near the bottom of Pinnock Hill and the Lewknor and Aston

Rowant crossroads" (Figure 8.8). Further that "the present road through Tetsworth is

narrow, confined, steep and very inconvenient" and to rectify this

problem "it is necessary to excavate

and lower the hill and to take down some buildings". Finally the Act placed the road from the New

Inn, Stanton St John, through Bayswater to Headington, into the care of the

trust. The properties in Tetsworth to be

purchased and demolished were a farm house, granary, stable and two cart sheds

along with three cottages owned by Miss Charlotte Weston, two messuages and a

shop belonging to Richard West and two gardens belonging to the Swan Inn, owned

by William Hall. Engineering work seems

to have started in 1823 when the accounts record that £698 was expended on work

to improve Stokenchurch Hill, £402 on improvements at Tetsworth and Postcomb

Hill and £306 on the new road by Bayswater to Stanton. Expenditure at Stokenchurch rose to £1,449

and at Tetsworth and Postcomb to £2,088 in 1826 when the trust also purchased

the houses from Richard West for £490.

It was not until 1829 that the purchase of Miss Weston's property was

completed for £492.

8.6 4.2 Other Engineering work

McAdam favoured the use of

flints for the bed of the road. Flints

are available locally and had apparently been used previously since large,

unbroken flints remain along the path of the old road down Stokenchurch Hill,

abandoned in 1826. In his report to the

Henley Road Trust (RUTV 7) McAdam urged the trustees to pay the extra cost for

flints since they performed better than other types of ballast. In 1826, Sam Jordan was paid for several

batches of material including £30-6s-0d for digging and carting 300 yards of

flint. The Parish of Aston earned

£23-6s-8d for "breaking flints",

presumably using labour from the poor of the village. The base of the road may have been stone with

a surfacing of gravel but fine material accumulated on the surface,

particularly when scrapings were not removed.

This meant that during the summer large clouds of dust were thrown up by

vehicles (see the cloud behind the coach in Figure 8.10a). The Stokenchurch

surveyors seem to have adopted the same technique as their colleagues on the

Bath Road and watered the surface during the summer. A new water cart, costing £60, was purchased

for the Begbroke section of the road in 1822.

Following the decline of

traffic after 1840, the turnpikes became reactive rather than being the

initiators of new work. The Stokenchurch

Trust consented to a cutting under the Woodstock Road to carry the proposed railway

from Tring to Oxford in 1853. In 1861

they allowed the UK Electric Telegraph Company to erect telegraph poles along

17 miles of road at an annual rent of Is per mile of road. They disputed the width of the railway bridge

erected at Chilworth in 1864 but recommended to the Watlington & Princes

Risborough Railway Company that the road traffic in 1869 was insufficient to

make building a bridge at the Lambert Arms in Aston Rowant essential. The bridge at Islip was in a poor state in

1871 and in 1876 the Thames Valley Drainage Company informed the trust that

they would be rebuilding the bridge which carried the turnpike over the river

at Islip. Finally, the trust chose not

to object in 1877 when Mr George Morrell sought permission to erect a steel

girder bridge over the road linking his properties on Headington Hill.

8.6.5 Toll Gates

8.6.5.1 The Main Gates

Gates were located at a small

number of strategic points along the turnpike road so that the maximum number

of tolls could be collected with the least expenditure. There was normally a tollhouse adjacent to

the principal tollgates so that a collector was always on hand to levy

travellers. The trustees had powers to

erect side gates across roads that led onto the turnpike road. These were let with the nearest main gate and

were probably only manned during part of the day, a simple shelter usually

being provided for the collector. The

minutes book for the trust from 1740 record that at this time there were three

main toll-gates on this road; at Yamton on the Woodstock road and at Wheatley

and Stokenchurch on the London road.

By 1778 the gate at Yamton was

being referred to as the Begbroke Gate.

This may not indicate any change of position since the earliest OS map

shows the tollgate at the Yarnton crossroads, where the modem dual carriageway

begins. The simple stone cottage is now

incorporated into the pub, formally called The Grapes but renamed The Turnpike

in the 1990s (Figure 8.11). This was

described in sales literature as stone and slated with four rooms, outhouse and

garden. The weighing engine, erected in 1791, was housed in a shed and there

were two long gates and a short gate. A

side gate controlled access to the lane leading to Kidlington. The various lanes connecting the main roads

from Oxford to Woodstock and Kidlington, allowed traffic to evade tolls at

Begbroke. In November 1814 the trust

erected a side gate at Campsfield, later referred to as the Bladon Bar (Figure

8.11). There were two huts for the toll

collector, presumably located close to where the modern dual carriageway ends. The Kidlington Trustees were worried that

travellers were using Langford Lane to avoid tolls and were causing undue

damage to this road. The Stokenchurch

Trustee installed a side gate across Langford Lane (now the southern boundary

of the airfield) in 1828 and provided a shelter for the collector at a cost of

only £12-6s-9d. This was later improved

since in 1878 the gate included a stone built tollhouse with a tiled roof

(Figure 8.11).

The Wheatley Toll-house was

located beside the bridge over the Thame, some distance east of the town. Following improvements to the bridge, the

Wheatley Gate was moved to the other end of the bridge in 1804. Mr Parsons was paid £86-11 s-0d, being half

the cost of erecting the new turnpike house, weighing engine and gate; the

county who were responsible for the bridge paid the remainder. When the trust closed, the tollhouse was

described as stone with a tiled roof, two bedrooms, two sitting rooms, a

kitchen and garden; this was the largest of the tollhouses on this road. The

weighing engine was used to check for over-weight waggons and the

toll-collector kept the fines. The

gatekeepers were given powers to levy 20s per cwt overweight in 1770 (JOJ). The

value of these fines may be judged from the fact that when the Wheatley

weighing engine was under repair for a short period, the trustees allowed John

Swane the lessee £20 for "the loss

sustained". One long gate and

one short gate formed this turnpike.

The earliest tollhouse at

Stokenchurch was near the top of the hill but in 1746 Thomas Ratford, who

leased the tolls, erected a new building nearer Stokenchurch. On Jefferys' map of 1768, on a map of 1824

and on the earliest OS maps the toll-bar is shown to the west of Stokenchurch

village. Soon after the trust was

established, the main Stokenchurch Gate appears to have had a weighing engine

to check for overweight waggons. This

was repaired in 1771 and in 1782 was replaced by William Braden, a carpenter

from Henley. In 1860, towards the end of

the life of the turnpike, the tollgate and weighing engine were moved once more

to the top of the hill, near the Red Lion.

When the trust closed the tollhouse was described as brick-built and

tiled with two rooms, pantry, hovel and garden; this made it the smallest of

the trust’s tollhouses. At the final auction of materials following demolition

of the buildings, two long gates and two side gates were offered for sale.

8.6.5.2 Other Gates

The records mention a gate at

Cheney Lane in 1778. This may have been

erected following the Act of 1762, in which year the income from tolls almost

doubled. The Cheney Lane Gate consisted

of a bar and chain with a sentry box for the collector; presumably the

collector lived close by. It was removed

in 1781 when the Headington road was under consideration but a side gate was

re-erected here in 1839 for a short period.

Under the Act of 1778 the trust were empowered to erect a tollhouse and

gate on the Islip branch. John Pamcott,

a Headington carpenter, erected the toll-gatherer's accommodation at Islip

Bridge on the eastern bank of the river Ray.

It cost £69 and judging from a contemporary sketch by Mrs Davenport was

a simple stone cottage. The ford beside

the bridge had been used to cross the river in summer but the trustees closed

this, obliging all travellers to pass through their gate or turnstile. Later improvements to the drainage deepened

the river channel making the ford impassable by the late 19th century (VHCO 6,

206).

As traffic into Oxford grew the

trustees sought to erect another gate on their new road through

Headington. A site close to the

Headington windmill, at the eastern end of land belonging to John Harding was

chosen for the new tollgate. This is now

the crossroads at the centre of modern Headington but the older village was a

little further north (Figure 8.11). The building contract was let for £323 to

John Cooper, a mason, and James Rose, a carpenter, both from Wheatley. By January 1826 the gate and weighing engine

were completed and the brick tollhouse with a tiled roof, 2 sitting rooms, a

bedroom and a scullery, had been built within a large garden. The iron weighing engine was in a wooden

building with a tiled roof and there were two long gates and one short gate. Additional costs were incurred in 1827 when

Rose was paid £4-5s-4d for a new privy at Headington and £11-2s-0d for a toll

board, and toll bar at the side-gate in Headington Field. George Hicks received £4-10s-0d for "writing the table of tolls" and

John Allsop £31-10s-0d for a pump and painting the boards. A second side-gate was erected across the

lane leading to the turnpike from Headington Quarry and another across Barton

Lane. Tolls were initially taken by

Thomas Phelps who was later lessee of the tolls until 1834. In the 1841 census, Mary Ann Phelps (aged 69,

his widow?) lived at the Britannia Inn a short distance from the turnpike.

Following the decline in

traffic after 1840, the trust considered changing the position of its turnpikes

east of Oxford. Previous suggestions for

a gate between the Royal Oak and Stoke Lane, Tetsworth, had concluded that it

would only yield £75/a. However, in the

new situation desperate measures were necessary and in 1841 the trustees began

to consider new gates between Tetsworth and the Three Pigeons on Milton Common

and another near Stowood. The trust

eventually resolved to build only the Tetsworth Gate but could not afford a

substantial building of the quality of that at Headington. A simple, narrow, single-storey brick cottage

was quickly erected by Mr Holland at Tetsworth for only £44 and a single long

road gate and single pedestrian gate were erected. This cottage survived as a domestic property

until 1998 when it was demolished and replaced by a modem house.

8.6.6 Toll Income

8.6.6.1 Tolls & Traffic

The basis of the tolls changed

as the trustees tried to better specify the users and minimise toll

avoidance. The first Act of 1719 allowed

charges of 1s-6d for a coach & six and 1s for a coach & four or a wagon. A horse not drawing anything was 2d, oxen

were charged at 10d a score and sheep 5d a score. The charges fell in 1740 in line with a

general cut in tolls on adjoining turnpikes.

After 1778 the basis for charging was simply the number of horses; 3d

for those drawing, 1d for those not. In

1788 the charge for a horse drawing rose to 4d and the 1824 Act (Figure 8.12)

allowed for up to 5d to be charged on a horse drawing a vehicle although until

1827 the toll actually remained at 4d.

The financial problems led the trustees to seek powers to charge 6d for

a horse drawing in 1845. The toll for a

typical coach with four horses was therefore 1s for most of the first century

of operation, rose to 1s-4d in 1788, 1s-8d in 1827 and 2s in 1845. A toll ticket was valid for the whole day on

the roads of a particular trust but travellers had to pay tolls at gates of at

least two other turnpike trusts between London and Oxford. Double tolls were charged on Sundays after

the 1778 Act but this was discontinued after 1796.

There are no surviving records

of the number of vehicles passing each tollgate. However, the total income from leasing tolls

of about £5,000/a in the 1830s is equivalent to about 1200 tickets per week for

a typical coach & four. The traffic

in 1740 would be equivalent to just less than 200 tickets per week indicating a

six-fold increase in traffic over the century.

From receipts during the periods when the trust took the toll collection

into its own hands, the revenue seems fairly constant on a month-by-month

basis. A note in the minutes of 1806

states "18 wagons on wheels of 16

inches broad pass and repass on this road every week. Great weight carried by these are detrimental

and illegal weight can not be checked"

8.6.6.2 Toll Collection

Originally the trust would have

employed its own toll gatherers and raised loans against the future income from

this. However, like most trusts it would have discovered that managing the

collection of large amounts of small change at remote locations was not easy

and the toll income fell below expectation. By 1770 it is clear that the trust

was looking to contract out the collection of tolls. The accepted system was

that annually the trustees auctioned a lease for the collection of tolls at

each of the main gates. The potential lessees

bid against each other in anticipation of what income they could expect from

tolls during the coming year. In the 18th century the auction was at the Crown

in Wheatley, where the trustees held most of their meetings. However, during the 19th century the event

was moved to the more prestigious surroundings of Oxford Town Hall. The auction was generally advertised in the

local newspaper, Jackson's Oxford Journal (Figure 8.13b).

During the century after 1740

the income from leasing tolls increased ten-fold. The Stokenchurch Gate, at the eastern end of